TRANSCRIPT

INTRODUCTION

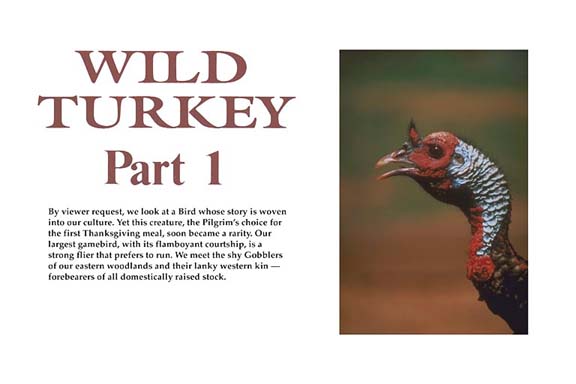

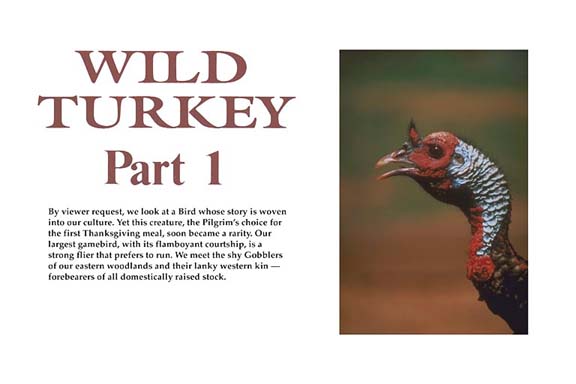

I am Marty Stouffer, the Wild Turkey is one of our most American birds. Though it mistakenly bares the name of a foreign country. It was common enough and so highly thought of that Benjamin Franklin wanted it proclaimed our national emblem. It nearly defeated the Bald Eagle in a vote by congress.

But the bird that the pilgrims served as their main course in 1621 had vanished from Massachusetts by the mid-1800 over shooting, the clearing of it's woodland habitat and the loss of a staple food to chesnutblight made this largest of the north America Game Birds one of the rarest.

Today the Wild Turkey has made a come back. It is found in every state except Alaska. But what do we really know about our familiar Thanksgiving symbol? Lets take a look at this strong flyer which prefers to run. This shy and wary bird with it's flamboyant courtship ritual. Lets get more aquatinted with the "Wild Turkey"

TRANSITION TO TITLE/ DAYBREAK

Its spring time here in the Oz ark mountains of Arkansas. This oak-hickory forest with an under story of Dog Wood and Redbud is perfect Wild Turkey habitat.

The lengthening day signals the start to one of the most colorful courtship rituals in nature. The females, the hens, watch as the males called, Gobblers or Toms, began to parade. We will return to these wild birds, first lets visit a farm down in the valley.

TRANSITION TO FARM

Lets compare the Wild Turkey to the Turkey we already know. The domestic Turkey gobbles all year long, rather then just in spring. Its head and neck are more covered with corenculated skin. The snood which hangs over its bill is much longer. It has a smaller brain and can only survive in captivity. Wild Turkeys are large, gobblers average 17 pounds, hens about ten. But domestic Turkeys are huge. A gobbler can way up to 50 pounds.

All Turkeys started out brown, but in recent years selective breeding has created the domestic White Turkey, the bird we put on our Thanksgiving table today. Why white? So that any remaining unpluked pin feathers are invisible to the consumer.

The Turkey is the most important live stock developed in North America But our story is about a bird of a different feather. The Wild Turkey its far more alert. Its neck and legs are longer and its body more streamlined. Adult males have a beard. The beard grows four to five inches a year, and is up to a foot long on three year old gobblers. But because it only gets so long it is not an accurate measure of age. It might look like hair but the beard is a tuft of modified feathers. This hen has a beard but only about one in twenty hens have one.

These are eastern Wild Turkeys, the bird the pilgrims served at the first Thanksgiving. The Toms and Hens spend most of the year apart and use a variety of vocalizations to locate one another for mating season. A gobble can be heard from up to a mile away. But other calls can only be heard a few feet.

This is a pulmonic puff, it is similar to sounds made by smaller cousins, the Grouse. A receptive hen crouches to be bred and a gobbler climbs on the hens back to fertilize her. But the dominate gobbler insists on his right to do all the mating. These yearly males called Jakes are usually are chased away by the Toms. But the yearling hens called Jennies join in the breeding.

The Eastern Wild Turkey is one of the six sub-species which have developed as a result of varied habitats. Since two types are only found in Mexico we'll be concentrating on the four types native to the US. The Eastern, Florida, Rio Grand, and Minims. The Eastern Wild Turkey is the most wide spread, it lives throughout the entire eastern half of America. When the hens go off to lay an egg in their nest or to forage the Toms follow.

TRANSITION :TURKEYS IN FLORIDA

The Florida Wild Turkey lives only in the Everglade state. It's the smallest of the four types. Except for size it differs little from its cousin the Eastern Wild Turkey, which also has tail feathers dipped in chestnut brown or buff.

Every flock has a dominate gobbler. The spurs on his lower legs indicate his age more accurately then does his beard. The spurs grow about half of an inch a year. They also go from rounded at one year to blunt at two years, to sharp at three years to very sharp at older then three years. Nearly all Turkeys live and die within 5 miles of where they hatched. But a foraging flock may wonder widely. They feed in the yearly morning, rest and sometimes take a roll in the dust in midday and then they forage again until roosting time at sunset.

The Wild Turkey is most often found in hard wood forest habitat, with grassy openings and plenty of oaks to supply acorns. However the bird has adapted to a wide variety of habitats, ranging form wooded swamp land to aired grass land like here in western Oklahoma.

TRANSITION TO: SUNSET

The Rio Grand Turkey lives form northern Mexico up through Texas and Oklahoma. Shorter legs and a cream colored tail tip distinguish it.

The Rio Grand is closely related to the South Mexican Turkey, which was domesticated by the Aztecs about two thousand years ago. The Indians hunted with arrows that had feathers made from turkey quills and points made from Turkey spurs.

Apparently they got tired of chasing the wild birds and began to raise them in captivity. The Spanish conquistadors took the turkey home with them in fifteen hundred. It became a delicacy spread across Europe and reached the table of King Henry the VIII . It was mistaken for the African Ginny foul which had been imported from the Turkish Empire.

So, for a while both birds were called Turkey foul. English settlers brought the domesticated version back to this continent, and so our most American bird bears the name of a foreign country.

TRANSITION TO: COLORADO

Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona are home to the Miriams Turkey. Of our four Turkey types it has the whitest romp and tail tips, and thus looks most like the domestic Turkey. Cougars are only one of the Turkey's predators. It is also hunted by Hawks, Owls, Eagles, Foxes, Bobcats and coyotes.

To protect all of that delicious breast meat Turkeys have excellent hearing and eyesight. They are the wariest of all game birds.

And though large they are not easy to catch. The Turkey can take off quickly and fly up to fifty miles an hour for a short distance.

Like all four types these Miriams remain constantly alert.

As many Wild Turkeys as we have today we once had even more. When Europeans first arrived in America there were an estimated ten million Wild Turkeys.

The bird immediately became an important food source for the settlers. This led to exploitation as hunting continued relentlessly Wild Turkey populations declined for three centuries. By 1920 the Wild Turkey could no longer be found in half of its original range. There was great concern for its loss as a game bird.

These biologist with the Arkansas game and fish commission are building a blind as the first step in capturing and transplanting Turkeys. In 1937 congress established a fund for national wildlife restoration and wildlife agencies began wide spread research programs.

After years of trial and error the turning point came with the idea of transplanting wild stock to restore turkey populations. But trapping the cautious birds was difficult. The use of a canon net powered by rockets or moorters was a major breakthrough in solving this problem. Turkeys are baited with corn right up to the hidden net.

While team mates run to get the truck loaded with crates one biologist clams the birds. Untangling feet and feathers is no easy task. The birds are upset but unhurt.

The amazing adaptability of the Turkey is what makes transplanting so successful. Also aided by hunting restrictions America's Wild Turkey population has increased from a low of 20,000 to over two million that is ten thousand percent in the last half century. It now lives in every state but Alaska.

This hen being banded before release in a new area is part of an effort that is one of the greatest success stories in wildlife management history. Some early restocking involved crossing domestic Turkeys with wild birds. It spread disease and may have polluted gene pools.

Still many of domestic Turkeys have been released intentionally to breed with wild ones. And some wild blood has been used to produce the so called game farm bird, a cross breed , though it may resemble its wild kin it has a larger white rump and tail tip and shorter legs. Its head is smaller with a less pronounced dulap and far fewer caruncles then the domestic Turkey. But the game farm bird is not much better at surviving in the wild then is its plump domestic cousin.

The real Wild Turkey is a far more graceful creature then either the barn yard or game farm breeds. Life in the wild keeps it more alert yet, they can all interbreed because there is only one species of Turkey. Which includes all wild and domestic types.

TRANSITION TO: RIVER

The Wild Turkey can live for twelve years if it avoids hunters and predators and if it can find food. Acorns are its main diet. A large gobbler may eat a pound of food a day.

This is the feeding call, it is not used to call each other to food but rather to keep the flock properly spaced. They pluck grasses and grapes catch grasshoppers and beetles and scratch for seeds and tubers. There diet is so varied it is almost easier to say what they don't eat.

The squirrel is one of the main competitors for the acorns but Turkeys will often find and steel their cash. The Red headed woodpecker has a better plan it hides an acorn off the ground in a tree crevice.

Another Acorn eater is the TuftidTit Mouse, and the Chipmunk can carry off a dozen at a time in its cheek pouches.

In spring time the only thing more important then food is mating. The long centered tail feathers identify this Jake. Jakes do join in the fighting, especially when hens are near. But a Jake will usually not fight a gobbler.

A Tom with a beard approaches the beardless Jake. The Jake meets the challenge. Anything can happen in nature in a reversal of the established social order the Jake drives the gobbler away from the hens.

TRANSITION TO SUNSET

During the last hour before sun down a Turkey flock finishes feeding and searches out a roost for the night.

After flying up they change limbs several times then settle down and preen.

Turkeys roost together for safety also for safety they usually change perches nightly. But they may return to the same tree if other good sights are not available.

There is much more to be learned about our largest upland game bird. Next time we will continue to study the Wild Turkey.

I'm Marty Stouffer. Until then, enjoy our "Wild America"